Gerald Farca, doctor of philosophy in English literary studies/video game studies published a new book an the topic of Utopian, Dystopian and Anti-Dystopian Worlds presented to Players in Video Games and how Players react to those Worlds.

With permission of the transcript Verlag and of Gerald Farca we proudly present an Extract of his newly pusblished Book. The concerning Extract „THE FLUX OF IMAGES AND THE PLAYER’S CREATION OF THE AESTHETIC OBJECT IN Metro 2033“

Re-imprint with permission of transcript Verlag (2018, Bielefeld).

Wiederverwendung (bzw. Wiederabdruck) mit Genehmigung durch den transcript Verlag (2018, Bielefeld).

Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-4597-2

PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-4597-6

https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839445976

Gerald Farca, born in 1983, did his doctorate at the University of Augsburg

(English Literature) and is a member of the Augsburg Cultural Ecology Research Group. In 2016, the digital culture and game studies scholar worked as a visiting researcher and lecturer at the Center for Computer Games Research of the IT University in Copenhagen.

THE FLUX OF IMAGES AND THE PLAYER’S CREATION OF THE AESTHETIC OBJECT IN Metro 2033

It has been clarified so far that representational art — and the genres of SF, utopia, and dystopia inparticular (through their games of estrangement) — denies direct access to the empirical world. Instead, representations involve the appreciator in creative games of make-believe. They urge him into imaginings of a certain kind and the player to action and grant access to their worlds through acts of ideation. This feedback oscillation between fictional and empirical world is largely encouraged by the creation of images and their negotiation as the player closes the blanks between the perspectives he encounters and co-creates. I have previously outlined the player’s creation of images with the example of Journey, and I now wish to go into further detail by resorting to Iser:

The imagistic vision of the imagination is… not the impression objects make upon what Hume still called ‘sensation’; nor is it optical vision … it is, in fact, the attempt to ideate … [vorstellen] that which one can never see as such. The true character of these images consists in the fact that they bring to light aspects which could not have emerged through direct perception of the object.[1]

The discussion of image creation in the act of play becomes of benefit to understand the player’s venture into dystopia. It will not only illuminate how he is able to decipher the distorted dreamworlds but, in addition, will clarify the mechanisms behind the emancipatory window the genre offers — when the player catches a glimpse of the truth behind the experience and of the opaque nature of his empirical surroundings.

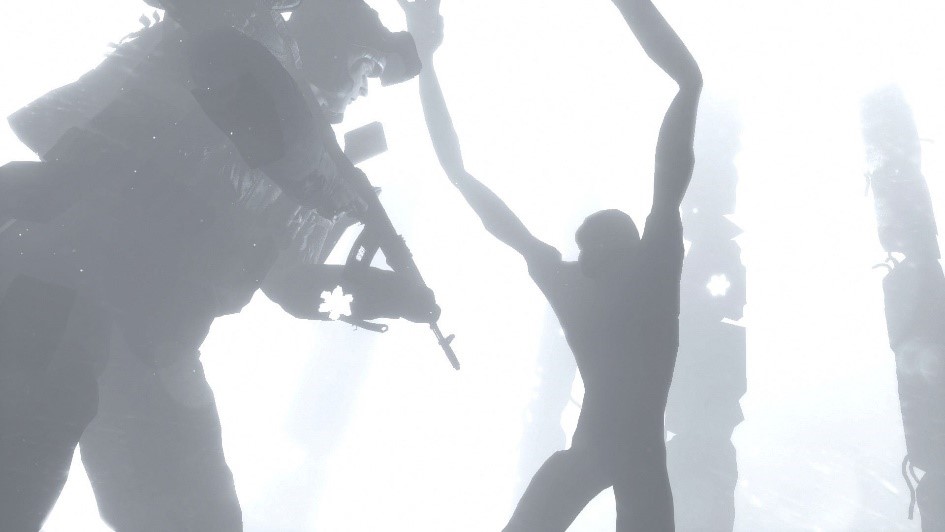

Metro 2033 does not deviate from this fact, and it would be hard to deny the naturalness of its aesthetic effect—sending the player on acathartic journey to enlightenment and having him ideate the images that compose and arise from his experience. These are in constant flux and their ever-changing signifieds urge the player to reconsider his previous imaginings and actions. In this respect, the tower at the game’s beginning and the image of the Dark Ones are of considerable importance. For, as Iser would say, they urge the player to imagine something that their iconic signs have not yet denoted but what is nonetheless guided through that denotation. Denotations transform into connotations, guided by the structural finesse of the game’s strategies, which allows the player to see the gameworld in a different manner and to create unexpected connections to his empirical surroundings.[2]

Figure 16: The image of the tower will ideate in the player’s mind and grant new insights into both the gameworld and the empirical world.

Perception and ideation are thus “two different [yet not mutually exclusive] means to access the world“: the former requiring an object’s “presence,” the latter its “absence or nonexistence.”[3] Although video games differ in this respect from literary works, as the player perceives large parts of the world (similar to the spectator or the viewer, whereas the world of a book can only be imagined), it is still necessary for him to ideate the truth behind these impressions and interactions. Such an enterprise will ultimately lead to the creation of the aesthetic object, whose initial “insubstantiality … spurs on the reader’s [/player’s] imagination” and induces him to partially complete “its shape.”[4] The creation of images, thereby, is by no means an arbitrary process but is guided by the textual positions and strategies that demarcate the reader’s journey and which formulate the “lines along which the imagination is to run.”[5] Following this train of thought, the strategies of a game become of fundamental importance to the participation process, since they guide the player on the lines of the ergodic and the imaginative, and set him in a dialectic with the work’s implied player.

The Blank and Its Ideation-Inducing Function as Positive Hint or Negation

To better understand the player’s acts of ideation, let me again resort to Metro 2033 in which the player takes on the role of twenty-year-old Artyom and embarks on a dreamlike journey of disclosure and disguise towards a mysterious tower. The tower is where the plot begins, at the story’s end, and eight days into the future. Artyom and Miller are about to finish their mission of dealing with the Dark Ones, a race of hostile creatures that through their psychicabilities induce nightmares in human beings and attack their stations. The first perspective segments contribute to this image. The player is about to reach the surface of what used to be Moscow and puts on his gas mask when a shadow, resembling a werewolf, bids him welcome to a frozen world. The threat is palpable, and once the player reaches the tower, his military convoy is attacked by vicious creatures. These first moments of the prologue (after which the game jumps back in time) introduce the player to the gameworld of Metro and anticipate future events. They are pregnant moments that create a space of uncertainty (indeterminacy) and function as “existential presuppositions” that, similar to the opening of a novel, indicate what can be found in this world and what is still to come.[6]

What the game achieves by doing so is not simply enabling the player’s understanding of this world but setting him on a journey towards the truth. This journey is structured by the form of indeterminacy I have termed the blank. Blanks, as Iser argues, “are the unseen joints of the text, and as they mark of schemata and textual perspectives from one another, they simultaneously trigger acts of ideation on the reader’s part.”[7] In doing so, the blank controls communication with a text/game and sets into motion the perspectives (segments)[8] encountered and created by the player. The drive for completion is here intertwined with that for combination, and this process of “passive synthesis”[9] induces the reader/player to slowly build up a gestalt, to create consistency by closing the blanks between the signs/perspectives.[10] The blank, as such, not only prompts the reader/player into imagining something that is not — the absent image upon which the player can act,not the reader—but it also structures this process in a decisive manner.[11]

Devising certain strategies, choosing how to proceed in a game, or imagining the gameworld’s particulars and plot details designate processes that are fuelled by the blank’s structure. In this form it is akin to what Doležel calls “positive (hints)”[12]—that is to say, it helps the player comprehend the plot and the game’s ludic structure and enables him to make informed decisions from these deliberations. In Metro 2033 this means understanding that the Dark Ones pose a threat and that for the sake of the game world and to complete the game, it is important to tackle the goal of defeating them, while comprehending how it could be done. The strategies of the game inform this process, and various perspectives aid the player’s comprehension, while virtualised potentialities enable him to actualise certain imaginings he deems possible and fruitful to enact.

This first function of the blank is complemented by what Doležel calls “negative (lacunae)”[13]—and herein lies the blank’s “aesthetic relevance.”[14] It is when play is at its most exciting that any attempts at “good continuation”[15] in the comprehension process and the act of play are shattered. This is not to say that in order to create aesthetic complexity a game should be unplayable. But what it should do is have the player ponder problems, his tactics, and not present him with premature solutions to both ergodic and imaginative issues. In such cases, blanks “break up the connectability of the schemata, and thus they marshal selected norms and perspective segments into a fragmented, counterfactual, contrastive or telescoped sequence.”[16] The result is a confusing array of perspectives that often contradict eachother and stand in opposition in an intricate game of agôn. As such, they withstand convergence/synthesis—and this runs against the player’s habitual dispositions in that his expectations of the game are shattered, or at least refuted, while he tries to solve the conflicts he is presented with.[17]

Such hindrances to play may occur in basic and more complex forms. For now, however, it suffices to say that art (or at least complex art), “impedes the acts of ideation which form the basis for the constitution of meaning”[18] and spurs the appreciator into creating a sequence of images that move on one another. In constant flux, they negotiate what is presented and inconflict and what is created by the player, and devise an unprecedented newness. This occurs through “various types of negation,” which “invoke familiar or determinate elements only to cancel them out”[19] and coerce the reader/player into discarding previously composed images. First degree images turn into those of a “second degree,”[20] and it is the latter to which readers/players respond most intimately. For the potential of a perennial response lies in one’s own creations, through acts of negotiation and revision and by imagining the unthinkable.[21] The player’s increased involvement in a game intensifies these games of proximity and distance, there is no doubt, by testing and validating the created images through ergodic efforts and acting upon them.

Metro 2033 is a well-suited example to illustrate these issues and to address the guiding function of the blank as well as the ideation-inducing hindrance of negation. When the plot moves back eight days in the past, the player has already glimpsed the hostile world that awaits him. First impressions have formed, and these continue to be informed by perspective segments once we set out to discover Artyom’s home station Exhibition. The section begins in Artyom’s room, where postcards of the old world are pinned to a wall. He is informed that a man called Hunter is on his way to the stationand sets out to find him. On the way there, the player is made familiar with life in the Metro. There is chatter about disease and mutant attacks, while a child cries in the background. People in Exhibition blame the Dark Ones for their current situation, mentioning how they damage their prey’s minds through hallucinations. The existential fear of the Other is palpable in every respect, and the player passes a hospital area with men wounded by the attacks. What can be the solution to these issues, the player may ponder. For the situation is desperate and the station will no longer endure it.

It is obvious that these perspectives contribute to the negative image of the Dark Ones formed in the prologue, and further insights intensify these impressions. Finally, the player meets Hunter, who seems to know Artyom, as he brings him a postcard of the Statue of Liberty to complement his collection. Hunter is a high-ranking Polis Ranger and constitutes the first important character perspective, with a clear motto: “If it’s hostile, you kill it.”[22] The conversation is interrupted by a sequence in which the mutants attack. The player quickly gathers a weapon and ammunition, tensely awaiting the upcoming action. Exhibition is saved for now — in a brutal skirmish — and an additional perspective that complements the horizon of past perspectives is created through the player’s actions. For now, the situation seems clear: The Dark Ones pose a threat that needs to be dealt with, and the perspectives the player has gathered and co-created strengthen this insight. Various blanks were closed in the process, which guided the player’s involvement in the game, and led to the premature solving of the conflict. These deliberations and actions are further propelled by another perspective created through the informational distance between Artyom and the player. Although these share a similar point of view (first person) and most of the action Artyom conducts (except in cut scenes), the player does not know Artyom. He lives in a world that is unfamiliar to the player, which is emphasised by Artyom’s retrospective narration of the events leading up to the tower. This arrangement of affairs leads to the creation of the most interesting blank between the two, which comes to the fore at the game’s end.

Blanks in VGNs thus arise between the perspectives the player encounters in the game world and co-creates through his actions. They are closed by the player’s acts of ideation (and in imaginative games of alea), which are informed by his world knowledge and contribute to his understanding of the game world, and also to his ability to perform in it. The strategies of the game organise this involvement, as they structure “both the material of the text [the repertoire of the game, the familiar context it draws on] and the conditions under which the material is to be communicated.”[23]

The conditions thereby refer to the aesthetic arrangements of the perspectives, which are cancelled once the experience of the game is narrated afterwards. What this means for the strategies is important, since they help the player understand the game world through employing his real-world knowledge but, additionally, expose it to meticulous scrutiny. They thus constitute the juncture with the empirical world—and so familiar norms, conventions, or references to other fictional worlds are reorganised horizontally in the game’s perspectives and by virtualising potential actions and processes. Consequently, it is only through the player’s acts of ideation that these blanks can be closed.[24]

The Player as Wanderer Between Sensorial Impressions and Playful Actions, Themes and Horizons

The process of understanding the fictional game world and creating connections to the empirical world is thus informed by “a background-foreground relationship, with the chosen element in the foreground and its original context in the background.”[25] This is to say, familiar norms and conventions “establish a frame of reference” and background for gameplay. As they are liberated from their original surroundings, however, they are depragmatised in the fictional game world and allow for “hitherto unsuspected meanings.”[26] Such a relationship is similar to “that of figure and ground in Gestaltpsychology”[27] and helps the player not only to comprehend the plot on a basic level, but also the levels of concept or significance.

To do so, the reader/player creates a “primary gestalt [that] emerges out of the interacting characters and plot developments,”[28] the game world occurrences, and the player’s actions within it. This primary gestalt is more diverse[29] than it could be in a novel or film, because different players create a great variety of plots arising from the same story (if the game allows them to). However, at times the creation of the primary gestalt runs into hindrances, as the games of agôn juxtapose seemingly incommensurable perspectives.

As a consequence, the creative function of negation begins to exercise its effect, which is complemented by the vivid games of mimicry Metro 2033 plays with the player. These doublings and distortions contribute to the primordial force of the fictive and begin to affect the player’s involvement on a basic plot level. I have clarified before that the perspectives help the player get his bearings in the gameworld, but they may also stand in conflict to one another and negate themselves. This is because, similar to reality, watching a film, or reading a book, playing a game confronts the player with a panoply of vistas or perspectives, out of which only a fragmentary number can be discerned at any given moment. These are nonetheless “interwoven in the text[/game] and offer a constantly shifting constellation of views”[30] that bewilder the player. The “theme” thereby designates “the view” or action the player is “involved with at any particular moment.”[31] It is substituted by additional themes that emerge in the course of play and moves into the background and the “horizon”[32] of previously encountered/enacted perspectives. The horizon of past perspectives thus includes both the inner perspectives of the text/game and the outer perspectives, which link the game to the empirical world, and conditions the player’s subsequent actions and imaginings based on the information he has gathered before (from the fictional and empirical world).[33]

Metro 2033 aggravates these games of agôn with a distorted dreamworld in which the true nature (or meaning) of the perspectives remains oblique. This is the case with the created image of the Dark Ones and the current gameworld situation that induces the player to handle the supposed threat. Such is the inevitable conclusion at this moment of play as the player draws from the horizon of past perspectives to compose it. Yet this image is fragile and will change, since with new perspectives, new impressions inform the player’s acts of ideation.

The continual interaction of perspectives throws new light on all positions linguistically manifested in the text, for each position is set in a fresh context, with the result that the reader’s attention is drawn to aspect hitherto not apparent.[34]

This statement gives a viable explanation as to why player actions are prone to assume different meanings in the aftermath of their execution—for example, when the player of The Walking Dead feels guilty about actions he previously deemed noble but which, through the encounter with new perspectives, turn out to be quite the contrary, or at least ambiguous. Consequently, with each new perspective—whether it is a player action, a character telling her news, a sign or gameworld process, “a retroactive effecton what has already been read [/played]”[35] is provoked, which results in potential “enrichment, as attitudes are at one and the same time refined and broadened.”[36]

Iser has called this process of continuous revision the reader’s “wandering viewpoint,”[37] an insightful and romantic term that is, nonetheless, not sufficient for the player. Because what he experiences rather resembles the venture of a wanderer between sensorial impressions andactions, between the floating of the spectator’s imagination and the ergodic participant’s navigation of and action within the gameworld. Such a feeling is unknown to a reader/viewer—think of how the player moves the virtual camera and catches a glimpse of an extraordinary event or discovers parts ofthe world that require his intervention. The perspectives he thereby encounters and co-creates are mapped to an entire panorama of sensorial impressions and actions that compose the horizon of perspectives that inform his subsequent actions and their potentiality (for players gain a feeling for what they can do in a game based on their previous knowledge/experience). This process, as Iser has remarked for the reader, is driven by a constant alternation between “retention and protension,” between what was and what is about to come (once theplayer acts).[38]

What follows from these observations is that the reader/player’s expectations are either confirmed by the newly encountered/co-created perspectives (this narrows down the semantic potential of the text/game; and to a degree the ergodic one) or they are frustrated and renegotiated in the flux of further perspectives in games of alea. The second option predominates in the literary text (in aesthetically complex literature) and forces the reader to constant reshaping of memory and the restructuring of the aesthetic object, when alea breaks open the semantic veil of the text and evokes the games of ilinxin the reader.[39] Such an initial frustration and semantic ambiguity occurs as well in Metro 2033 in the constant renegotiation of the image of the Dark Ones, whose formation is influenced by perspectives that stand in opposition. These hinder the player’s comprehension of the plot (and choice making in this respect) as well as his acts of ideation on the level of significance. They nonetheless drive the player to a constant renegotiation of the aesthetic object.